1.

Orang Asli (Malaysian Itas: Kensui and Jehai)

2.

Ati Ita (Philippine Itas: Ayta, Ati, Agta, &

Iraya, North Ita)

3.

Mamanwa Ita (Philippine Ita, South Ita)

4.

Papuan

The same can be said with the separation for the two groups

of Itas in the Philippines, the Mamanwa and North Itas. We can probably deduce

from this that the separation of the two Philippine Ita populations was due to

at least two major island groups that formed the Philippines during those ice

ages. If we look carefully at the Philippine map including the seabed, you can

almost make out at least two island groups. The Luzon – North Bisaya island and

the South Bisaya - Mindanao island. Again, these long period of physical

separation probably also caused the large genetic distance.

It’s interesting that the Papuans and Atis are close to each

other; I would have expected the Atis and Mamanwas would be closer due to

proximity. Perhaps the Mamanwas had a “bottle neck” founder populations similar

to the Mlabri, meaning, the founders of the Mamanwa before the separation came

from a small group of the bigger Ita group (bottle neck).

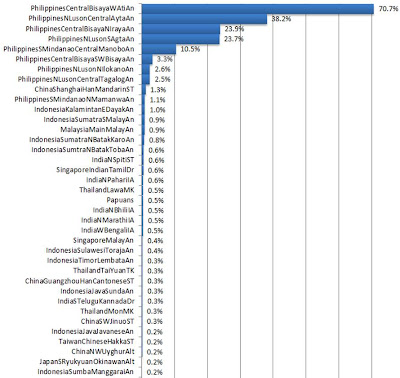

Figure 6: Mamanwa Gene Prevalence

Figure 7: Ati Gene Percentage

Figure 8: Ati Gene

Prevalence

Figure 9

& Figure 10

bring in some inferences. The Ati & Mamanwa groups have only recently

admixed with the Malay speakers (Nusantao). This is likely since the

archaeological evidence of Malay settlements to ISEA are less than 5.5K BP. The

significant Papuan presence in the Ati samples is a surprise. As mentioned, the

four Ita groups have large separation. If it is true then the Papuan content is

of recent admixture. Were the Papuans and/or Atis able to develop maritime

technology (sea worthy ships)? The other possibility is that the Ati’s were the

founder source for the Papuans (and perhaps the Mamanwas); given the relatively

greater Ati diversity. Note the Mamanwas has 1.1% Papuan content. The Papuans,

on the other hand, has 99.2% Papuan, 0.5% Ati, & 0.3% Mamanwa. Whatever the

possibilities are, the Papuans, Mamanwas & Atis have significant

interactions in Luson, Bisaya, & Mindanao.

Note: Although percentage less than 0.25% maybe be a margin

of error in admixture analysis, I would not completely dismiss these results

since we are only comparing 55,000 SNPs compared to the millions unidentified.

For the moment, I will most likely not explore percentage less than 0.25%.

Figure 9: Mamanwa Admixture

Figure 10: Ati Admixture

Figure 11:

Papuan Gene Percentage

Figure 12:

Papuan Gene Prevalence

Figure 13:

Malaysia Ita Gene Prevalence

Figure 14:

Malaysian Ita Admixture

References

1. Yang X, Xu

S, The HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium (2011) Identification of Close Relatives

in the HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Database. PLoS ONE 6(12): e29502.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029502

2. D.H.

Alexander, J. Novembre, and K. Lange. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry

in unrelated individuals. Genome Research, 19:1655–1664, 2009

3. H. Zhou,

D. H. Alexander, and K. Lange. A quasi-Newton method for accelerating the

convergence of iterative optimization algorithms. Statistics and Computing,

2009.

4. Alexander

D. H., Lange K. (2011). Enhancements to the ADMIXTURE algorithm for individual

ancestry estimation. BMC Bioinformatics 12:246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-246.

5. Purcell S,

Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de

Bakker PIW, Daly MJ & Sham PC (2007) PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome

association and population-based linkage analysis. American Journal of Human

Genetics, 81.

6. Greenhill,

S.J., Blust. R, & Gray, R.D. (2008). The Austronesian Basic Vocabulary

Database: From Bioinformatics to Lexomics. Evolutionary Bioinformatics,

4:271-283.

7. Mijares,

A.S.B. et al. 2010. New evidence for a 67,000-year-old human presence at Callao

Cave , Luzon , Philippines. Journal of Human Evolution, 59:123-132.

doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.04.008.

8. Mijares,

A.S.B.2007. The Late Pleistocene to Early Holocene For-agers of Northern Luzon.

Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistoric Association 28:99-107.

9. Sagart, L.

(2002). Sino-Tibeto-Austronesian: An Updated and Improved Argument. BMC

Bioinformatics 12:246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-246.

10. Gaillard, J. C. and Mallari,

J. P. (2004), The peopling of the Philippines: A cartographic synthesis, Hukay:

Journal of the University of the Philippines Archaeological Studies Program 6.

11. Mijares, A.S.B. 2008. The

Peñablanca Flake Tools: An Unchanging Technology? Hukay 12:13-34.

12. Mijares, A.S.B. et al. 2010.

New evidence for a 67,000-year-old human presence at Callao Cave , Luzon ,

Philippines. Journal of Human Evolution, 59:123-132.

doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.04.008.

13. Dizon, E.Z. et al. 2002.

Notes on the Morphology and Age of the Tabon Cave Fossil Homo Sapiens. Current

Anthropology 43:660- 666.

14. Détroit, F. 2002. Origine

et évolution des Homo sapiens en Asie du Sud-Est: Descriptions et analyses

morphomé-triques de nouveaux fossiles. PhD thesis, Paris, France: Muséum

national d'Histoire naturelle.

15. Détroit, F. et al. 2004.

Upper Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Tabon cave (Palawan, the Philippines). Human

Paleontology and Prehistory 3:705–712.

16. Fox, R.B. 1970. The Tabon

Caves. Monograph of the National Museum of the Philippines. No. 1. Manila.

17. Barton, H., Piper, P.J.,

Rabett, R., and Reeds, I., 2009. Com-posite hunting technologies from the

Terminal Pleisto-cene and Early Holocene, Niah Cave, Borneo. Journal of

Archaeological Science 36:1708–1714.

18. Kaplan, M. R. et al. (2005).

Cosmogenic nuclide chronology of pre-last glacial maximum moraines at Lago

Buenos Aires, 468S, Argentina. Science Direct Quaternary Research 63

(2005) 301 – 315.

19. Kennedy, K. A. R. 1977. The

deep skull of Niah. AP 20:32-50.

20. Brothwell, D. R. 1960. Upper

Pleistocene human skull from Niah Caves, Sarawak. SMJ 9:323-349.

21. Lews, H et al. 2008. Terminal

Pleistocene to mid-Holocene occupation and an early cremation burial at Ille

Cave, Palawan, Philippines, Antiquity Volume: 82 Number: 316 Page:

318–335

22. Sieveking, G. de G. 1954.

Excavations at Gua Cha, Kelantan 1954. Part 1. FMJ 1 and 2:75-143.

23. Adi Haji Taha. 1985. The

re-excavation of the rockshelter of Gua Cha, Ulu Kelantan, West Malaysia. FMJ

30.

24. Zuraina Majid. ed. 1994. The

Excavation of Gua Gunung Runtuh. Malaysia: Department of Museums and

Antiquity.

25. Budhisampurno, S. 1985.

Kerangka manusia dari Bukit Kelambai Stabat, Sumatera Utara. Pertemuan

Ilmiah Arkeologi III, 955-984. Jakarta: Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi

Nasiona1.

26. Solheim, Wilhelm G.

Archaeology and culture in Southeast Asia : unraveling the Nusantao, (revised

edition), Diliman, Quezon City : University of the Philippines Press, 2006.

27. Purcell S, Neale B,

Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker

PIW, Daly MJ & Sham PC (2007) PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association

and population-based linkage analysis. American Journal of Human Genetics, 81.