The Ice Age

Before we embark on our journey, the basic understanding of

a great event that peaked at least twice during the migration of our ancestors

should first be understood. Theories surrounding the causes of ice ages are

still up for debate. The Earth’s wobble

and the amount of greenhouse gases are the main theories linked with the

occurrence of the ice ages. Ice

ages are marked by two periods, the glacial and interglacial. Glacial

periods are the period of colder temperatures while Interglacial are the relatively

warmer periods.

A glacial maxima happens during a glacial period when the

temperatures are at its lowest point; in essence it is the peak of an ice age.

Interglacial is basically the period between glacial maximas. As the

temperatures decrease, the Earth’s water accumulates as glaciers in the

northern and southern hemispheres; it is at these times when the polar ice caps

get closest to the equator. The source of water that form these glaciers are

mainly from the ocean, hence at a glacial maxima, the sea level is at its

lowest point which gives rise to shallow seabed and becomes what scientists

calls “land bridges”. The increase in ice in the European and Asian continents

and the emergence of land bridges especially in between continents, as

scientists know today, played a major role in the peopling of the world.

The last two glacial maxima had been estimated to be between

25,000 to 15,000 BP and 175,000 to 125,000 BP (Kaplan et al. 2005).

Timeframe

Another important vocabulary we need to have a basic

understanding of is about the two epochs. Geological epochs are geologic stratifications/timescales

involving different rock layers that form the Earth’s crust; the significance

of which is the present and last epochs provided many fossil finds that helps

in the understanding of the peopling of the world. The Pleistocene epoch spans

approximately 1.6 million BP to 10,000 BP. The next epoch is the Holocene and

spans up to the present time. The last two glacial maxima that happened in the

late Pleistocene and early Holocene may have played a significant role in the

peopling of the world.

Models of Migration in Southeast Asia

As scientists have explained, there are at least two great

migrations to the Philippines; the Itas and the Malay speakers. Gaillard and Mallari compiled the

various theories behind the peopling of the Philippines and of course it

touched on the surrounding areas within Southeast Asia. From what I observed,

the PASNP may support Manuel’s and Bellwood’s theories where the origins of the

Malay speakers may have been from mainland South China; more specifically, I

believe we are from Southwest China.

Ita ang Unang Tao sa Luson, Bisaya, at Mindanao

Itas are the first people to settle Luson, Bisaya, &

Mindanao

The Itas (Negritos)

were the first to settle Island Southeast Asia (ISEA). The famous Tabon Man

was discovered by Dr. Robert B. Fox in 1962 in the Tabon Caves of Palawan

island is one proof; it was dated at 22.5K BP. Although Scott states in his book that

the Tabon Man is not Ita I believe

the opposite is true. My reasoning is simply by process of elimination; all of

the archeological findings that links to the Austronesian speaking people

(Nusantao) in ISEA have never been more than 5.5K years old (Bellwood).

If not the Itas nor the Nusantao, who else can the Tabon Man be? Aside from the

Tabon Man, a new discovery by Dr. Armand Salvador B. Mijares of what may be the

oldest human fossil find in Southeast Asia called the Callao

Man; the Callao Man has been dated 67K BP and scientists describes part of

the bones found to be similar to modern Itas. There are also other sites from

other islands as shown in Table 1;

this table shows the various archaeological finds in Southeast Asia linked to

the Itas.

BTW: I call the Negritos, Tasmanians, Orang Asli (Negritos),

Australoids,

Australo-Melanesian, & Melanesoid as Ita

including all other group of people with the phenotype pigmented skin,

frizzy/curly hair and typically shorter in stature than the average East Asian

population. Ita is a term that my parent and my parents parents thought us who

these people were/are (at least in the Philippines at the time). This is what what

the Northern Itas call themselves also; the spelling may have evolved over

time. I have Ita blood myself and Itas are part of the fabric that makes a Malay.

Since there are no known land bridges that can connect

Palawan to mainland Luson (see satellite image from Google), we can infer that,

at least for the Itas in the Philippines (except Palawan), they have reached

the islands by means of a raft or some sort.

Figure 1: Snapshot of Philippines with the visible but submerged

land bridges connecting Palawan to the Sunda

shelf (from Google maps). The added highlights shows where humans would need a

raft of some sort to cross to the next island and reach Luson.

Table 1: List of Archaeological Finds Linked

to the Itas

Number

|

Date

(BP in thousand) |

Item

|

Site

|

Island

|

Country

|

Reference

|

Remarks

|

1

|

65.7

|

human third metatarsal

bone

|

Callao Cave

|

Luson

|

Philippines

|

Mijares et al. 2010

|

"Negrito"

|

2

|

40

|

deep skull

|

Niah Cave

|

Kalamintan

|

Malaysia

|

Kennedy 1977

|

"Tasmanians"

|

3

|

37

|

human tibia

|

Tabon Cave

|

Palawan

|

Philippines

|

Détroit et al. 2004, Fox

1970

|

"Melanesoid"

|

4

|

25.5

|

flaked artefacts and

charcoal

|

Callao Cave

|

Luson

|

Philippines

|

Mijares 2007, 2008

|

|

5

|

22

|

charcoal

|

Tabon Cave

|

Palawan

|

Philippines

|

Fox 1970

|

|

6

|

14.5

|

frontal bone

|

Tabon Cave

|

Palawan

|

Philippines

|

Dizon et al. 2002, Fox

1970

|

|

7

|

13.9

|

small flake assemblage

|

Ille Cave

|

Palawan

|

Philippines

|

Lewis et al. 2008

|

|

8

|

10.7

|

projectile points made

of bone and stingray spine

|

Niah Cave

|

Kalamintan

|

Malaysia

|

Barton et al. 2009

|

|

9

|

10

|

twenty-seven burial

remains

|

Gua Cha

|

Peninsular

|

Malaysia

|

Sieveking 1954, Adi 1985

|

"Melanesian"

|

10

|

10

|

male skeleton

|

Gua Gunung Runtuh

|

Peninsular

|

Malaysia

|

Zuraina 1994

|

"Australo-Melanesian"

|

11

|

7.5

|

twelve disturbed

skeletons

|

Sukajadi Pasar

|

Sumatra

|

Indonesia

|

Budhisampurno 1985

|

"Australo-Melanesian"

|

12

|

6.5

|

burials

|

Moh Khiew Cave

|

Peninsular

|

Malaysia

|

"Australo-Melanesian"

|

|

13

|

6.5

|

red painted bones, two

skulls

|

Wajak

|

Java

|

Indonesia

|

Dubois 1890

|

"Australo-Melanesian"

?

|

There are many surprising results regarding the Itas from a

previous blog

which I will expand here. First, there seems to be at least four unique Ita

populations in Southeast Asia.

1.

Orang Asli (Malaysian Itas: Kensui and Jehai)

2.

Ati Ita (Philippine Itas: Ayta, Ati, Agta, &

Iraya, North Ita)

3.

Mamanwa Ita (Philippine Ita, South Ita)

4.

Papuan

Figure 2: PC1 vs PC2

Plot (Zoomed)

These separations are demonstrated through the genetic

distance produced by Admixture, the correlation analysis, principal component

analysis and dendrogram. These large Ita separation is likely a very long period

of separation from each other. It is odd though that the obvious phenotypes did

not change much (pigmented skin and curly/frizzy hair – another topic for

another blog J ).

Initially, the Itas populated Southeast Asia including ISEA through land

bridges that appeared as an effect of ice ages. These land bridges lasted for a

very long time since population movements are not as quick as it is today;

we’re talking about thousands of years. Then later, the sea level rose and the

land bridges disappeared to where they are today. Since the Itas and most

people in the world did not have the technology to travel long distance by sea;

the genetic separation began and since the genetic distances are large, it must

have been thousands of years (long period).

I have updated the dendrogram from the previous blog using “complete” method. The “ward” method gave results inconsistent with the Fst table. I have also added some cluster box equal to 9, representing the 9 cluster populations.

I have updated the dendrogram from the previous blog using “complete” method. The “ward” method gave results inconsistent with the Fst table. I have also added some cluster box equal to 9, representing the 9 cluster populations.

Figure 3: PASNP Dendrogram (K=19)

The same can be said with the separation for the two groups

of Itas in the Philippines, the Mamanwa and North Itas. We can probably deduce

from this that the separation of the two Philippine Ita populations was due to

at least two major island groups that formed the Philippines during those ice

ages. If we look carefully at the Philippine map including the seabed, you can

almost make out at least two island groups. The Luzon – North Bisaya island and

the South Bisaya - Mindanao island. Again, these long period of physical

separation probably also caused the large genetic distance.

It’s interesting that the Papuans and Atis are close to each

other; I would have expected the Atis and Mamanwas would be closer due to

proximity. Perhaps the Mamanwas had a “bottle neck” founder populations similar

to the Mlabri, meaning, the founders of the Mamanwa before the separation came

from a small group of the bigger Ita group (bottle neck).

Figure 4: Ita

Admixture

The Mamanwa and the Ati Itas have significant admixture with

each other (Figure

5).

Mamanwa also have admixture with the 2nd group of migrants, the Malay

speakers; it shows an admixture range from 1.2% to 1.5% for the Ilokano,

Bisaya, & Tagalog samples while the Manobo (Mindanao Nusantao) clearly

admixed with Mamanwa at a higher percentage, 6.6%. The Ati Itas & Mamanwa

gene is present (albeit small amount) with all the countries in Southeast Asia

(Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, South China, Indian) in the PASNP data. This gene

presence is probably proof that they have once lived among the mainland East

Asians – Mon-Khmer, Nusantao, Tai-Kadai, & Sino-Tibetan, at the least and

South Asians (Indians). Note that there is a paper out there shows the South

Indians (Dravada speakers) to be another Ita group. (Vedoid) but the 4 Ita

groups in Southeast Asia are definitely distinct from the ancient Dravada

speakers.

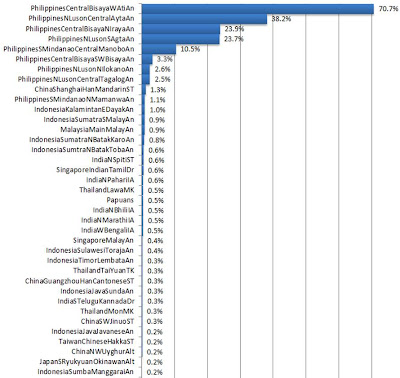

Figure 5: Mamanwa Gene Percentage

Figure 6: Mamanwa Gene Prevalence

Figure 7: Ati Gene Percentage

Figure 8: Ati Gene

Prevalence

Figure 9 & Figure 10 bring in some inferences. The Ati & Mamanwa groups have only recently admixed with the Malay speakers (Nusantao). This is likely since the archaeological evidence of Malay settlements to ISEA are less than 5.5K BP. The significant Papuan presence in the Ati samples is a surprise. As mentioned, the four Ita groups have large separation. If it is true then the Papuan content is of recent admixture. Were the Papuans and/or Atis able to develop maritime technology (sea worthy ships)? The other possibility is that the Ati’s were the founder source for the Papuans (and perhaps the Mamanwas); given the relatively greater Ati diversity. Note the Mamanwas has 1.1% Papuan content. The Papuans, on the other hand, has 99.2% Papuan, 0.5% Ati, & 0.3% Mamanwa. Whatever the possibilities are, the Papuans, Mamanwas & Atis have significant interactions in Luson, Bisaya, & Mindanao.

Note: Although percentage less than 0.25% maybe be a margin

of error in admixture analysis, I would not completely dismiss these results

since we are only comparing 55,000 SNPs compared to the millions unidentified.

For the moment, I will most likely not explore percentage less than 0.25%.

Figure 9: Mamanwa Admixture

Figure 10: Ati Admixture

Figure 11:

Papuan Gene Percentage

Figure 12:

Papuan Gene Prevalence

Figure 13:

Malaysia Ita Gene Prevalence

Figure 14:

Malaysian Ita Admixture

References

1. Yang X, Xu

S, The HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium (2011) Identification of Close Relatives

in the HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Database. PLoS ONE 6(12): e29502.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029502

2. D.H.

Alexander, J. Novembre, and K. Lange. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry

in unrelated individuals. Genome Research, 19:1655–1664, 2009

3. H. Zhou,

D. H. Alexander, and K. Lange. A quasi-Newton method for accelerating the

convergence of iterative optimization algorithms. Statistics and Computing,

2009.

4. Alexander

D. H., Lange K. (2011). Enhancements to the ADMIXTURE algorithm for individual

ancestry estimation. BMC Bioinformatics 12:246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-246.

5. Purcell S,

Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de

Bakker PIW, Daly MJ & Sham PC (2007) PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome

association and population-based linkage analysis. American Journal of Human

Genetics, 81.

6. Greenhill,

S.J., Blust. R, & Gray, R.D. (2008). The Austronesian Basic Vocabulary

Database: From Bioinformatics to Lexomics. Evolutionary Bioinformatics,

4:271-283.

7. Mijares,

A.S.B. et al. 2010. New evidence for a 67,000-year-old human presence at Callao

Cave , Luzon , Philippines. Journal of Human Evolution, 59:123-132.

doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.04.008.

8. Mijares,

A.S.B.2007. The Late Pleistocene to Early Holocene For-agers of Northern Luzon.

Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistoric Association 28:99-107.

9. Sagart, L.

(2002). Sino-Tibeto-Austronesian: An Updated and Improved Argument. BMC

Bioinformatics 12:246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-246.

10. Gaillard, J. C. and Mallari,

J. P. (2004), The peopling of the Philippines: A cartographic synthesis, Hukay:

Journal of the University of the Philippines Archaeological Studies Program 6.

11. Mijares, A.S.B. 2008. The

Peñablanca Flake Tools: An Unchanging Technology? Hukay 12:13-34.

12. Mijares, A.S.B. et al. 2010.

New evidence for a 67,000-year-old human presence at Callao Cave , Luzon ,

Philippines. Journal of Human Evolution, 59:123-132.

doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.04.008.

13. Dizon, E.Z. et al. 2002.

Notes on the Morphology and Age of the Tabon Cave Fossil Homo Sapiens. Current

Anthropology 43:660- 666.

14. Détroit, F. 2002. Origine

et évolution des Homo sapiens en Asie du Sud-Est: Descriptions et analyses

morphomé-triques de nouveaux fossiles. PhD thesis, Paris, France: Muséum

national d'Histoire naturelle.

15. Détroit, F. et al. 2004.

Upper Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Tabon cave (Palawan, the Philippines). Human

Paleontology and Prehistory 3:705–712.

16. Fox, R.B. 1970. The Tabon

Caves. Monograph of the National Museum of the Philippines. No. 1. Manila.

17. Barton, H., Piper, P.J.,

Rabett, R., and Reeds, I., 2009. Com-posite hunting technologies from the

Terminal Pleisto-cene and Early Holocene, Niah Cave, Borneo. Journal of

Archaeological Science 36:1708–1714.

18. Kaplan, M. R. et al. (2005).

Cosmogenic nuclide chronology of pre-last glacial maximum moraines at Lago

Buenos Aires, 468S, Argentina. Science Direct Quaternary Research 63

(2005) 301 – 315.

19. Kennedy, K. A. R. 1977. The

deep skull of Niah. AP 20:32-50.

20. Brothwell, D. R. 1960. Upper

Pleistocene human skull from Niah Caves, Sarawak. SMJ 9:323-349.

21. Lews, H et al. 2008. Terminal

Pleistocene to mid-Holocene occupation and an early cremation burial at Ille

Cave, Palawan, Philippines, Antiquity Volume: 82 Number: 316 Page:

318–335

22. Sieveking, G. de G. 1954.

Excavations at Gua Cha, Kelantan 1954. Part 1. FMJ 1 and 2:75-143.

23. Adi Haji Taha. 1985. The

re-excavation of the rockshelter of Gua Cha, Ulu Kelantan, West Malaysia. FMJ

30.

24. Zuraina Majid. ed. 1994. The

Excavation of Gua Gunung Runtuh. Malaysia: Department of Museums and

Antiquity.

25. Budhisampurno, S. 1985.

Kerangka manusia dari Bukit Kelambai Stabat, Sumatera Utara. Pertemuan

Ilmiah Arkeologi III, 955-984. Jakarta: Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi

Nasiona1.

26. Solheim, Wilhelm G.

Archaeology and culture in Southeast Asia : unraveling the Nusantao, (revised

edition), Diliman, Quezon City : University of the Philippines Press, 2006.

27. Purcell S, Neale B,

Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker

PIW, Daly MJ & Sham PC (2007) PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association

and population-based linkage analysis. American Journal of Human Genetics, 81.